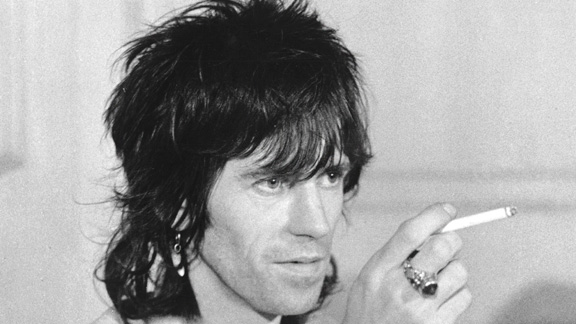

Robert Altman/Getty Images/1970

Keith Richards can be frank about heroin, but for athletes just that cigarette would be a PR crisis.

At the grocery store a couple of weeks ago it struck me that with the playoffs over, the draft passed, the whole darned league locked out and -- most importantly -- a plane ticket out of town for the next morning, it was time to do something I used to really enjoy: Read.

You know, like an actual book, for fun, poolside.

There was no time for Amazon or the closing local Borders, but a few yards away near the customer service desk was a selection of about 50 books, 20 of which were for reading, as opposed to coloring in. Just one of those was not about murder, right wing versus left wing, business secrets or dieting. It was perhaps the 5,923rd memoir entitled "Life," but this one happened to be written by Keith Richards (and co-writer James Fox).

Back from vacation, and close to 600 pages later, my mind is swimming in sex, drugs, money, bragging, forays to Africa, drugs, car accidents, police stakeouts, a Bentley with secret drug compartments and life-saving military-grade glass, drawn guns, rented French mansions, a drowning, collapsed lungs, drugs ... the whole crazy carnival of the Rolling Stones. In "Life" (as in life) Richards demonstrates all the pizzazz that makes him a rock legend, the dedication to craft that makes him an historic guitarist and the self-centeredness that helps him bask, not cower, in a half-century of spotlight.

If he's holding anything back, it's hard to know what it might have been. Even the recipe for his favorite bangers and mash made the cut. Here is how he "raised" his first child, poor Marlon, who spent vast chunks of his youth alone in the attic of a Long Island mansion (being minded by binge drinkers while Richards was on tour or partying somewhere else). There's where he bought drugs, where he first had sex with band mate Brian Jones' girlfriend, how the Canadian prime minister's wife was a groupie. Here are the myriad ways Richards' most important business relationship, with Mick Jagger, has been roughed up again and again.

And, in a remarkable insight, he describes getting around a junkie's shortage of hypodermics in New York City in the 1970s by wearing a medical needle as a hat pin on his trip from London. Upon arrival, he'd check into the Plaza on Central Park South, then walk across the street to F.A.O. Schwarz:

If you went to the third floor, you could buy a doctor and nurse play set, a little plastic box, with a red cross on it. That had the barrel and the syringe that fitted the needle that I'd brought. I'd go round, "I'll have three teddy bears, I'll have that remote-control car, oh, and give me two doctor and nurse kits! My niece, you know, she's really into that. Must encourage her."

Tough talk

Richards' story is a macho one -- women play minor roles, ex-convicts are his real friends. He presents himself as a swashbuckler, entirely unafraid of pulling a gun (unlicensed, of course), throwing a knife, picking a fight or, for that matter, ingesting a mighty eight grams of pure Merck pharmaceutical grade cocaine -- the high lasted days -- on a dare.

There is no shortage of tough talkers in this world, but Richards stands way the hell out for keeping his tough guy hat on even when it's time to tell what actually happened.

Many of the most important relationships of his life -- with Jagger, with the family of his wife Patti Hansen, with the mother of his older children Anita Pallenberg, with record companies, promoters and drug dealers -- all got rocky and are all discussed in reckless specificity. He pilots his pen like he piloted his Bentley -- with a lot of scrapes. Let the chips fall where they may.

If there's value in honesty, this is an international treasure. That kind of truth won't please many PR experts and I'm sure the lawyers had conniptions, but you've got to hand it to the guy. He sure keeps things from straying too far from the truth, and that's exhilarating. What a lovely break from the saccharine sanitized version of things. It may be ugly, but at least it's real. And in the case of Richards, his frankness is informative. His rules are interesting. No mainlining the heroin, for instance -- only in the muscle. No crack. No freebasing. And only the absolute highest grade of everything. If the heroin gets out of hand, these are some remedies. These are the real stresses of the spotlight. This is what groupies mean to rock stars. This is what friendship feels like in the eye of the media hurricane.

And if we just accept that Richards lived by his own rules, we can skip the narcotics debate for a moment and get on with the business of digging into those fascinating rules. From the outside, the driving factors of his life were whether or not to do this or that drug. But from the inside, there's a rich tale of defining a musical style, keeping a band together against long odds and working obsessively to hone the sound. He'd stay up nine straight days not just to enjoy the drugs, but also to mix and re-mix this or that song. Despite all the drugs, the band went years without a week off.

There's universality, and maybe a touch of heroism there. That kind of work often drives success in all fields. A glamorous image and a drug problem ... those are by-products, not the recipe. It's the work that did the trick. But you have to dig deeper into the story to get to those goods. You have to accept your entertainers "warts and all," or you have to accept that you're living in a fantasy world.

And yet, there is all kinds of evidence that Richards' approach has more than succeeded. For one thing, this book is a best-seller. It earned him fawning coverage from the likes of, for instance, CBS News, where he earned warm chuckles from his interviewer while relaying tales of snorting his dad's ashes. I don't want to make it seem like he has always been accepted -- he was hounded by police officials and politicians through the years. But in terms of how the public views him, by now he has certainly carved out a big ol' chunk of real estate for himself to do essentially whatever he wants and people just keep right on celebrating him.

Richards reports that a few years ago the prime minister of England at the time, Tony Blair, wrote the world's most famous junkie a note saying "you've always been one of my heroes."

On YouTube, there's old footage of Richards on the nod, the woman with him dropping an ash into his hair, then, inebriated as she is, rubbing it in. The top-rated comment on that video calls him "beautiful." There he is tossing a TV off a balcony and they call him "so cool."

Warts and all works

Think about Keith Richards making his way into F.A.O. Schwartz. Let's say you were there, and you saw the whole thing. You might come away from that thinking "you know, that Richards really cares about his nieces and their careers."

And you'd be a dupe. He was putting up a cover story, and you fell for it.

That's bad for your dignity. Nobody likes being taken for a ride like that. (The opposite of that is what makes this account refreshing.)

Those kinds of little lies, however, persist in the NBA. Unlike music, in this sporty nook of the entertainment world, there is just no tolerance for the kinds of soul searching, personal struggles, addiction, partying and everything else that is part of some of the performers' lives. To the extent such personal stories exist in the NBA, the stories are most commonly ignored, covered up or simply left untold.

But the real deal stories hidden deep beneath the NBA are not just hidden by the PG-rated PR impulses of the league, but also by the media which only does a so-so job of teasing such stories out, and by players themselves.

There is a drastic shortage of players with Richards' devil-may-care approach to image-making.

Leeway for white entertainers

Richards is the toast of prime ministers and admired even for how he passes out inebriated on video.

Could you ever imagine any NBA player getting anything like that kind of leeway with the public?

I'm not saying Richards ought to have been scolded more by the public -- he has clearly been essentially perfect in his job of getting rock fans what they want, and I can only imagine the work that goes into keeping up a performance like that for so many years.

Instead I'm asking: What's with us? Why do we have vastly different expectations for the personal lives of different kinds of people?

How many millions of NBA fans would happily sit in the good seats and cheer like crazy for Richards, whether he had had a recent DUI or not?

Why do so many of those same people have no patience at all for DUIs in the NBA?

How did we get here, where Richards gets to show people how to really live, while NBA players living anything like him need to be taught a lesson by Richards fans?

I guess we tell ourselves it's about players needing to lead these healthy lifestyles to stay ready to perform athletic feats. But all kinds of players have proved again and again through the years that evidently you can stay out late drinking fairly often (Michael Jordan) or smoke some pot now and again (according to a New York Times report years ago, close to three-quarters of the league) and still play the best ball of a generation.

In another YouTube moment, some fan runs on stage while the Stones are rocking. Richards sees the guy coming, takes off his black guitar, grips it like a bat, and meets the running fan with a hard blow to the head. Then he kicks the startled-looking guy and wallops him again with the guitar. Looks like it hurts. The guy runs off after a couple of seconds. Richards glares at Jagger for good measure, puts the axe back on his chest, adjusts a knob or two, and rejoins "Satisfaction" in progress. The leading comment on that episode on YouTube is that this proves Richards is a great guitarist and the whole thing is "too funny."

You're telling me Ron Artest gets to pick up a chair and clobber a fan who runs onto an NBA floor and then keep right on playing basketball?

Of course, the issue I'm dancing around here is race. Predominantly white audiences accept things from white entertainers that they would not accept from others.

To me that's a point that barely needs defending, but as I can feel some of you getting a little tense, let me point out that the Stones' popularity itself proves this. Like Elvis before them, they essentially made careers out of mastering things black musicians had done before them.

"Benedictines had nothing on us," writes Richards of the band's formative period, huddled in a London apartment. "Anybody that strayed from the nest to get laid, or try to get laid, was a traitor. You were supposed to spend all your waking hours studying Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Howlin' Wolf, Robert Johnson."

The Stones found their early success strictly as a cover band -- covering black American musicians. Amazingly, that worked. They were a phenomenon first, and then someone told them they ought to consider coming up with their own material.

If Jimmy Reed and Little Walter were the masters of what the Stones were learning, why were white audiences going insane for the Stones but largely ignoring Little Walter?

Why have the rules been different for black entertainers?

That's not only a question for white audiences, but one that hangs over the NBA, where a code has emerged among players to skate by those rules. The code is, basically, keep all that crap private. Which has a certain sense to it, especially in the name of keeping players' images sanitized so as not to jeopardize corporate endorsements, which fascinate players, teams and leagues (as well as, it's worth noting, the Rolling Stones) alike.

As someone who cares pretty intently about the NBA, I don't mind that a lot of what's personal is kept personal. But I do mind that some of the stories told about the league are fabrications.

I'm not sure any NBA player has ever, officially, missed a game because of a hangover. But through the years we're talking about thousands of young men living on the road. You insult my intelligence.

More importantly, raise your hand if you can identify for me a player -- beyond the delightfully bold Stephen Jackson -- who talks openly about having been a gang member or a drug dealer. These are stories that matter. We know all kinds of the world's best players grew up in the times and places where crack and guns dominated. Players must have heavy stories about all that. Not to mention: Staying out of gang trouble simply must be a common NBA story. How do you do that? People need to know. Young NBA fans need to know. It's potentially heroic role-model stuff, and likely some of the toughest things many of these young men have ever done. Let's hear about it.

Did you miss the team bus because your childhood friend wigged out and you had to talk him back to sanity? We all get a little dumber when that's announced as "questionable -- strained quad."

If you learned about Bill Walton by watching TV over the past 20 years, you'd be amazed to learn that big charming goof in the mass-produced tie-dyes was once of interest to the FBI. (What could he do?) But he was, and in the annals of official NBA history you're virtually on your own to figure out why that might have been.

There's just a lot more nitty-gritty to the NBA than is discussed publicly. Some of what is lost is "dirt," this or that party-life mini-crime covered up in the name of protecting gleaming Boy Scout images and the profits they accrue. That's always going to happen. But a lot of what's lost is the real stuff that matters. Fans are fascinated to determine which players are jerks and which are saints. We all know that in real life such things can't be determined by tidy categories like who has had police run-ins. (When Carmelo Anthony explains that in his childhood, the cops were violent jerks and the drug dealers bought you sneakers; or Serge Ibaka, Leon Powe or Jimmy Butler get specific about their childhoods ... well now, this is a real conversation.)

And you can feel it. Some NBA players carry the weight of the world on their shoulders. Messed up family relations, money trouble, disease, violence, addiction, war ... whatever it is. And night after night the people charged with telling their stories ask them the same missing-the-point questions. And they answer them with platitudes. And everyone gets in their cars and drives home, connections unmade.

The Blueprint

It's all well and good for me to suggest young, mostly black NBA players should walk in the footsteps of the old, white, set-for-life Richards. They are held to different standards, facing different prospects. That's a real hurdle.

But since when do superstars shy from hurdles?

Jay-Z, with his book "Decoded," has shown what can be done. Working corners, selling crack, using guns and being ostentatious in telling young America all about every second of it ... he's the walking encapsulation of much of what most scares social conservatives.

"Baggy jeans and puffy coats," explains Jay-Z, "to stash work and weapons, construction boots to survive cold winter nights working on the streets." He reports he started dealing at 15 -- after he started carrying a gun. A guy named Dee Dee showed young Shawn Carter how.

Shortly after that, Dee Dee was murdered in a most gruesome fashion.

"You would think that would be enough to keep two 15-year-olds off the turnpike with a pocketful of white tops. But you'd be wrong."

"I've done some stuff," writes Jay-Z, "even I have trouble explaining."

He's not sugarcoating anything, but at the same time he's building connections with audiences of all colors.

In my notes from reading that book, somewhere around page 30 I wrote in all-caps: "I WOULD LIKE TO THANK JAY-Z FOR TAKING THE TIME TO BRIDGE ONE OF THE BIGGEST CULTURAL GAPS IN AMERICAN HISTORY."

In explaining himself in lyrics, in interviews and in a book, he honors the truth, and the audience, with the tougher particulars of his story, wrapped up with a hopeful tone. He's not crazy. He's not dangerous. He's just muddling through the challenges of life like we all are, admittedly living by a different set of rules than suburbia, much like Richards did.

And there he is, full of tales of the hustle of the Marcy projects and one of the most truly empowered people in entertainment. (Not to mention: an NBA minority owner.) He's not just a performer and a media executive, he's a voice that matters among intelligentsia, on the stage at the New York Public Library with Cornel West, with good seats at the inauguration of a president, and on and on.

Don't tell me it can't be done.

It's not weird to me that most NBA players just don't go there. In addition to being young and primarily just interested in playing basketball, that kind of honesty stirs up big hassles every time. Of course most NBA players, like most people, just avoid that kind of mess.

What is weird to me is that among NBA players just about nobody is leading. Fans still set the tone for what's acceptable, and the league and teams have responded with all manner of codes of conduct, punishment systems and dress codes and more that force players into some kind of 1950s-style "Leave It to Beaver" code of life. That's so comically out of step with the day-to-day reality of players today as to be flat wrong. What would be right would be to sync our expectations for players with the reality they inhabit.

And what's that like?

Maybe in the future the people who know it best will step forward to explain.

Source: http://espn.go.com/blog/truehoop/post/_/id/31319/the-keith-richards-school-of-public-relations

Kevin Russo Curtis Granderson Nick Johnson Javier Lopez Alex Hinshaw Ramon Ramirez

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen